The Heliocentric Worldview and God's Unconditional Love for Us

Having committed myself to a weekly private tuition arrangement (a rather bold experiment, in my view, for a nursing mum of a 2 month old baby--Dad's still complaining about booting him and baby out to the mall during the session), I came across the following Neil Postman while browsing the internet for suitable essays for teaching purposes. Entitled "Informing Ourselves to Death", this paper was given as a speech at a meeting of the German Informatics Society on October 11, 1990 in Stuttgart. A paper written late in his career, it was as interesting as I expected it to be. (I had read Amusing Ourselves to Death (1986) with much enthusiasm and Teaching as a Subversive Activity (1971) with much less--) His main thesis is that we are now living with a sort of cultural AIDS brought on by the information glut--one that's steadily reducing our ability to sort out truths from falsehoods, and to use information in a productive, problem-solving way that people in the past were (supposedly) much better able to.

Even though I am usually in basic or substantial agreement with Postman whose ruminations on the role of technology in our culture have taught me much, this is one paper in which I feel he has given in to too much overstatement. Take two examples:

The tie between information and action has been severed. Information is now a commodity that can be bought and sold, or used as a form of entertainment, or worn like a garment to enhance one's status. It comes indiscriminately, directed at no one in particular, disconnected from usefulness; we are glutted with information, drowning in information, have no control over it, don't know what to do with it.and

The point is that, in a world without spiritual or intellectual order, nothing is unbelievable; nothing is predictable, and therefore, nothing comes as a particular surprise.We can, however, still appreciate a more modest point and the way he expresses it: "technological change is always a Faustian bargain: Technology giveth and technology taketh away, and not always in equal measure. A new technology sometimes creates more than it destroys. Sometimes, it destroys more than it creates. But it is never one-sided."

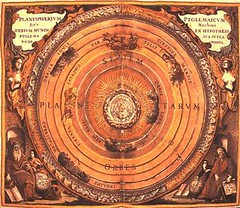

My main disagreement with his nonetheless interesting paper has to do with his suggestion that "before Galileo and Kepler, it was possible to believe that the Earth was the stable center of the universe, and that God took a special interest in our affairs. Afterward, the Earth became a lonely wanderer in an obscure galaxy in a hidden corner of the universe, and we were left to wonder if God had any interest in us at all. The ordered, comprehensible world of the Middle Ages began to unravel because people no longer saw in the stars the face of a friend." Postman seeks to contrast a pre-heliocentric (I mean the perspective), pre-scientific world where there was a more-or-less ordered and comprehensible worldview supposedly shared by most medievals, to one which was ushered in by the invention of the printing press and which continues with us today with the computer. The point of the contrast is that in the former world, information was scarce but "its very scarcity made it both important and usable," whereas in the latter, we have a glut of information--"what started out as a liberating stream has turned into a deluge of chaos."

Firstly, his portrayal of the medieval situation is simplistic and highly romanticised. His citing of impressive numbers (e.g. 11,520 newspapers in the US) that follow also does not convince me that I, an individual member of such a world, am desperately drowning in information to the extent of a kind of paralysis; I may read the local newspaper I subscribe to or the NY Times on the net, and not be in the least bit concerned about the remaining 11,519 'choices available'.

Secondly, and here's where I think Postman has made the biggest blunder in this piece: it has never been the case that mankind has in any way merited God's love. To suggest that the medieval had imagined himself worthy of divine favour because he was an inhabitant of earth which he understood as occupying the central place in the cosmos is, firstly, to be mistaken about how medievals thought of the significance of the geocentric cosmos. If anything, earth being at the centre also meant that earth was at the very bottom of the cosmos, where the dregs where, farthest from things heavenly. Furthermore, the Christian would know from the Bible that God's love for us is, and has been, and can only ever be, unconditional--because we are infinitely unworthy of it, just as He in His good pleasure chose the very rebellious, often disobedient Israelites to be His special people. To fancy otherwise would be presumption indeed.

If God has any interest in us--and He surely does--it is because of His good pleasure and grace. The heliocentric view of the world has properly replaced the geocentric one, but the lesson remains pretty much the same: God's unconditional love for us lowly, sin-stained wretches displayed for us in his Son who is at the centre of all things.

"But God, being rich in mercy, because of the great love with which he loved us, even when we were dead in our trespasses, made us alive together with Christ--by grace you have been saved--and raised us up with him and seated us with him in the heavenly places in Christ Jesus, so that in the coming ages he might show the immeasurable riches of his grace in kindness toward us in Christ Jesus. For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast. For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them." ~ Ephesians 2:4-10 (ESV)

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home